author: niplav, created: 2020-11-20, modified: 2025-01-04, language: english, status: in progress, importance: 4, confidence: highly likely

The Diamond-Square algorithm is a terrain-generation algorithm for two dimensions (producing a three-dimensional terrain). I generalize the algorithm to any positive number of dimensions, and analyze the resulting algorithm.

Libre de la metáfora y del mito

labra un arduo cristal: el infinito

mapa de Aquel que es todas Sus estrellas.

— Jorge Luis Borges, “Spinoza”, 1964

I learned of the diamond-square algorithm by reading through the archives of Chris Wellon's blog, specifically his post on noise fractals and terrain generation. The algorithm is a fairly simple and old one (dating back to the 80s), but not being interested in graphics or game programming, I shelved it as a curiosity.

However, a while later I needed a way to generate high-dimensional landscapes for a simulation, and remembered the algorithm, I felt like I could contribute something here by generalizing the algorithm to produce landscapes in an arbitrary number of dimensions, and that this would be a fun challenge to sharpen my (then fairly weak) Python and numpy skills.

The original (2-dimensional) diamond-square algorithm, in its simplest form, starts with a grid of numbers.

It is easiest explained visually:

For dimensions, do that, just higher-dimensional.

We start by initializing an n-dimensional space with zeros, and the corners with random values:

def create_space(dim, size, minval, maxval, factor):

space=np.zeros([size]*dim)

corners=(size-1)*get_cornerspos(dim)

space[*(corners.T)]=np.random.randint(minval, maxval, size=len(corners))

Here, get_cornerspos is just the one-liner

return np.array(list(itertools.product([0, 1], repeat=dim))).

We then intialize the variable offsets, and call the recursive

diamond-square algorithm:

offsets=[np.array([0]*dim)]

return ndim_diamond_square_rec(space, dim, size, offsets, minval, maxval, factor)

Now there are two possible variants of the generalized diamond-square algorithm: the Long Diamond variation and the Long Square variation.

Let's take a 3×3×3 cubical grid and think about how we can run the diamond-square algorithm on it.

One way of doing so would be to calculate the center of the cube as the mean of all the corners, and then the center of each face as the mean of its corners. The value for the midpoint of each edge is calculated from the midpoints of the edges and the centers adjacent faces.

I call this variant the Long Diamond variant. It performs two diamond steps and only one square step along the three dimensions.

But there's another way: Calculate the center of the cube as the mean of its corners, just as before. But now go directly to the edges and calculate their midpoints as the mean of the endpoints of each edge. Then, calculate the value of each face as the mean of the value in the center of the cube and the centers of the adjacent edges.

That is the Long Square variant: It performs one diamond step (computing the value for the center) and two square steps (for edges and for faces).

Consecutive diamond steps go from higher dimensions to lower ones, consecutive square steps go from lower dimensions to higher ones. There is one dimension where the values are "stitched together"—in the long diamond case it's the first dimension (on edges), in the long square step it's the second dimension (on faces). I guess one could also leave out the diamond steps together and calculate the center of the cube as the mean of the faces—zero diamond, very long square.

The algorithm starts out with a base case: If the space is only one element big, do nothing and return (assuming the value has been filled in):

def diamond_square_nd(space, size=None, offsets=None, stitch_dim=1, minval=0, maxval=255, factor=1.0):

if size==None:

size=space.shape[0]

if size<=2:

return

Next, some housekeeping to initialize values if they haven't been initialized: We want to know the dimensionality we're dealing with, and initialize the offsets to be zero:

dim=len(space.shape)

if type(offsets)==type(None):

offsets=np.zeros([1, dim], dtype=int)

Now we come to offsets. Remember way above in the two-dimensional

case, when after the first square step, we moved into a diamond step on

the smaller squares? offsets describes where the "left lower corner"

of those smaller squares is. We initialized it with zeros, that way we

start in a definite corner.

For the diamond step, we start with this function signature:

def diamond_rec(space, size, offsets, stitch_dim, minval, maxval, factor, subdim=None):

The only interesting parameter is subdim, which describes how many

dimensions the algorithm already has gone "down": It starts at 0, which

means that we take the center of space, and assign it the mean of

all corners.

dim=len(space.shape)

if subdim==None:

subdim=dim

If we've already handle so many dimensions that the next one would be the dimension at which we stitch things together, we return:

if subdim<=stitch_dim:

return space

The next part gets a bit tricky. We can't just, for every offset, add all

corners to that offset, scale it with the size, and say that those are

all the corners. That works iff subdim==0, in which case we don't have

to worry about handling faces of our space. (In that case we could write

corners=offsets[:, np.newaxis] + cornerspos[np.newaxis, :]*(size-1).)

Instead, something more complicated happens:

Within every offset, we have to (1) choose all possible dimensions we could fix to either zero or the maximum value, and then (2) generate all possible ways of fixing those dimensions to zero/maximum values.

(1) is sort of easy to visualize: If we have to assign the values to the faces of a cube, we have to generate all the centers of the faces and all the corners for each of those faces. For the top face we have to fix a dimension to the maximum, for the bottom face to zero, for the left face another one to zero and for the right one to the maximum, and so on for the front and back faces. (2) is a bit more tricky, but should be doable to imagine: If we instead can fix two dimensions, we can assign them 0 and the maximum each, independently.

Abbreviating for dim and for subdim, the resulting

structure should have have the size —for every c-dimensional direction, enumerate all

hypercubes in that direction

on the boundary of space, list all corners of that c-dimensional

hypercube, but use dim dimensions.

We create now an empty canvas for our corners, an object with the right dimensions but zero everywhere:

cornerspos=np.broadcast_to(np.zeros(dim), [math.comb(dim, subdim), 2**(dim-subdim), 2**subdim, dim])

cornerspos=np.array(cornerspos) # because broadcast_to returns readonly

For the sake of my sanity I'm going to write the following code in a very imperative style, Iverson forgive me.

occupied_counter=0

for occupied in it.combinations(range(dim), subdim):

unfixed_counter=0

for unfixed in it.product([0, size-1], repeat=dim-subdim):

cornerspos[occupied_counter, unfixed_counter, :][:, occupied]=get_cornerspos(subdim)*(size-1)

free=tuple(set(range(dim))-set(occupied))

cornerspos[occupied_counter, unfixed_counter, :][:, free]=unfixed

unfixed_counter+=1

occupied_counter+=1

So, with the previous setup this should be fairly understandable: We go through the dimensions that are "occupied" with the corners, and for the rest we set the values to all possible directions.

We then flatten out cornerspos one dimension to make it easier to handle:

cornerspos=np.reshape(cornerspos, [math.comb(dim, subdim)*2**(dim-subdim),2**subdim, dim])

Finally, we generate the corners by, for each offset, adding it to

all corners (basically creating the cartesian product of offsets and

cornerspos and then summing them):

corners=offsets[:, np.newaxis, np.newaxis]+cornerspos

But the resulting datastructure has a bad shape, so we flatten the first two dimensions into one:

corners=np.reshape(corners, [offsets.shape[0]*cornerspos.shape[0], *cornerspos.shape[1:]])

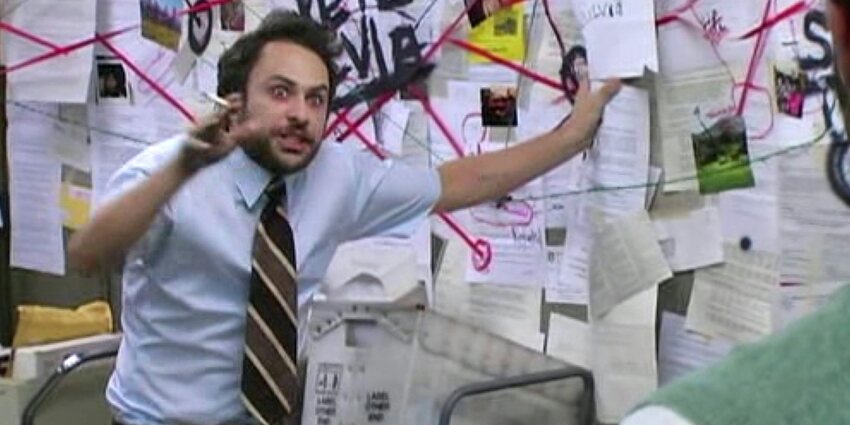

Code here. I think this is probably the 2nd-most beautiful code I've ever written, just after this absolute smokeshow.